The Shetland Isles

June 2003

The day we arrived was foggy, and after we settled in to the campsite at Levenwick, we spent the morning drinking coffee and watching the mist gradually lift, rolling about in the glorious landscape in front of us. In the afternoon, we set off for Sumburgh Head, but stopped at a disused quarry when we were nearly there - a colony of fulmars were going about their business.

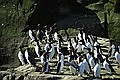

We spent some time there before tearing ourselves away to see the main attraction - the puffins and guillemots at the Head. Later, we laughed about our enthusiasm, as we found fulmars in residence at every outcrop and cliff in the Islands.

| Driving north across the Mainland, I braked hard and pulled in to the side as the colours of the lake and its vegetation hit me in the eyes. Yes, the water really was that intense deep blue. |  |

After I had finished trying to capture the scene photographically, I became aware of the amount of birdsong around me on the moorland. Several pairs of oystercatchers were in sight, a curlew flew around and a redshank was standing on a fence post a few yards down the road.

The bird life on the moors in Shetland seemed so much richer than their equivalent in North Wales or the Peak District. Everywhere we stopped, we saw oystercatchers and curlews, with redshank and wheatear appearing on closer examination. Is the abundant birdlife the result of the scarcity of predators (no foxes, badgers, stoats, weasels) or of humans?

Here, too, there were a pair or two of oystercatchers to scold you, and to perform the broken wing trick (with occasional over-acting!) if you strayed too close to their nest.

Everywhere were eider ducks, with the plain brown females shepherding chicks, while turnstones foraged among the seaweed.

On the way to Eshaness in the northwest of Mainland, we stopped for lunch at the village of Hillswick. As we ate our sandwiches on the pebble beach, we watched as a school of sandeels in the sea loch were harried by a group of divers, terns and a solitary black guillemot. The terns kept flying off with their beaks full to feed their young somewhere further up Ura Firth.

There are lots of seals around, generally lounging around on rocky outcrops. They seem to accept being observed by humans with wary equanimity, and can be equally curious about humans. You are wandering along a beach or around a headland, and suddenly you become aware that you are being observed - a head protruding from the waves disappears after a while when you stare back. Shortly, the seal pops up somewhere else to subject you to the same intense scrutiny.

Gannets are stars. Graceful in flight, elegant on their cliff ledges, and stylish in shape and colour. First close encounters were by boat around the cliffs of the Isle of Noss, where the awesome height and unusual rock formations formed a perfect setting for the birds. Guillemots provided the supporting cast.

A few days later, we took the ferry from Gutcher across the Bluemull Sound to Unst. In the northwest of the island is the peninsula of Hermaness, which ends in towering cliffs which are home to mainly gannets and puffins. From here, we could see the Muckle Flugga gannetry and lighthouse in the distance, the most northerly point of the British Isles.

The puffins, typically engaging and confident, were busily sorting out mates and burrows.

Walking back across the moorland, we were observed from every vantage point by Great Skuas, or "bonxies". Their colloquial name seems most appropriate to their arrogant, piratical nature. They were always present at the bird colonies throughout the islands, cruising around, casting a cold eye on their potential victims.

Back at the campsite, a colony of gulls were nesting in an adjacent field, and were visited on two occasions by a bonxie. The first indication was when most of the gulls took to the air with loud cries as the pirate glided in, but their demonstration proved to be no deterrence. The bonxie swooped on a nest, took a chick and flew off leisurely, pursued at a safe distance by several gulls.

As we drove south across Unst, a hill which ended at the sea in cliffs came into view. It had a strange brown appearance, as if no rain fell on it. This was the hill which has been described as a botanist's dream - the Keen of Hamar. On closer examination, the barren surface was found to be speckled with plants, most in flower. These were plants which could tolerate the outcrop of serpentine of which the hill was composed. Here were alpine plants which normally lived in mountains much higher, together with others which were particularly adapted to this exotic environment. This included Edmondstons Chickweed, found nowhere else but on Unst.

From Unst, we returned to Yell, to our campsite beside the cemetery of St. Olaf's church. From here, we looked down to the sandy bay backed by dunes, called the Sands of Breckon, and the rocky promontery from which rose yet more cliffs. We could see the remains of aViking settlement protruding through the grass, among which were nesting rock pipits and ringed plovers.

We stood in the fading light of Shetland midnight before the ancient bulk of the broch, trying to make out the bat-like flutterings of the petrels as they arrived.

The tiny birds, long distance travellers to the Southern Ocean for our winter, often induced awe in observers of their apparent frailty and indestructibility amongst the worst that the ocean could do far out to sea. Here they were, arriving after a day's labour out at sea, to take over parental duties regarding their single egg, seemingly quite unfazed by the crowd of people surrounding their chosen home - a 5000 year old fortified house, whose walls were full of the crevices that the petrels needed.

As the light faded, birds arrived more frequently, materialising out of the darkness suddenly to circle around the broch's walls, dodging the odd human in their way with ease. Then there would be a brief flutter on the wall before disappearing into the opening leading to their life's partner and the egg of the year.